Story Structure: The Key to Writing a Book

There’s a lot to consider when writing a book: tone, word count, plot, character, setting, theme, style, and so on.

Think of story structure as a series of road signs posted along the journey of your story. Think also of story structure as the rails that keep you from straying onto the meandering path that can often lure a writer from the actual course of the story.

Story structure creates the underpinning of the book.

Without it, narratives have no form, and the plot has no provocative way to move the reader from one moment to the next or from one scene to the next.

The essential element of story structure is what we were all taught in school: beginning, middle, and end. If there is a fixed star in the universe of storytelling, this is it. Every story has a beginning, middle, and end. Every scene has a beginning, middle, and end. But how these elements are dramatized- how they are conceived and shaped, juxtaposed and presented to a reader- is up to you.

Think of the story structure as a hanger. It holds and shapes an infinite variety of shirts, blouses, dresses, coats, and suits. One of the most important structures you will learn about is the Symmetrical Storybook Paradigm. This is the structure that underlies most of the best-loved storybooks.

You will see that no matter how carefully you labor over your book’s tone, word choices, plot, character, setting, theme, and style, you must thoroughly grasp its structure if you wish your book to succeed.

Indeed, you will find that an expert command of structure is the key to writing a successful book.

Like an architect who draws a blueprint before building, a writer should plan his story before writing it.

What is so important about the Symmetrical Storybook Paradigm and its variations is that they can apply to almost any plot and sequence of events in a story.

Whether the story is a fairytale, a folktale, or any other tale doesn’t matter.

It doesn’t matter whether the conflict occurs is person-against-self, person-against-nature, or person-against-person.

Whether the story is told in the first person or third person doesn’t matter.

The Symmetrical Storybook Paradigm can apply to most storybooks.

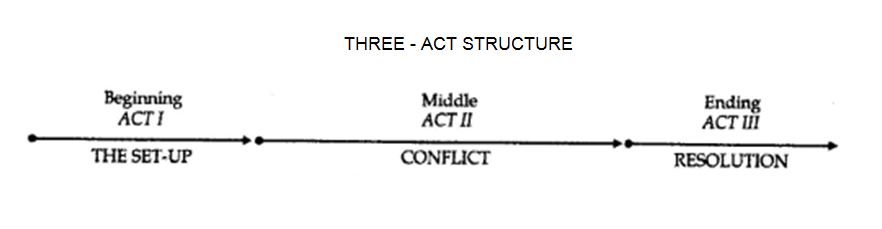

The Three-Act structure

The Three-act Structure means having a beginning, middle, and end.

The Three-act Structure means having a beginning, middle, and end.

The opening is the first act. The characters and problems are introduced, along with an inciting incident, or turning point, that moves the reader from Act 1 to Act 2.

In Act 2, the main character takes more action and even more action to solve his problem. The act most often culminates in a low moment when all feels lost.

Act 3, contains the resolution of the problem or the ending. Once the problem set out at the beginning of the book is solved, the story is over, except for tying up any loose ends.

Form and Story Structure

Is the opening solid and compelling? Has the setup and description gone on too long?

Does the plot build to a pivotal point? Does the ending grow out of the story? Does it evoke an emotional response and make the reader want to reread it?

Are there strong page-turners? Does the resolution come on page 30 or 31? Is there a nice twist or punch line on page 32?

Your story must focus on your main character. The reader wants to follow the main character’s dreams without regret to what others think. Have them stand up for their convictions despite other opinions.

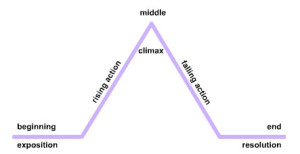

Basic Dramatic Structure

According to A Handbook to Literature by William Flint Thrall and Addison Hibbard, the operatic structure is divided into distinct, identifiable parts.

- The rising action

- Exciting force

- Conflict and complications

- Climax

- Falling action

- The reversal

- The resolution

- The last moment of suspense

Whether the classic Greek dramatist was dealing with comedy or tragedy, these critical story elements did not change. Twenty-five years later, the structure is still valid.

Remember that the middle of your story moves through the conflict and complications, the climax, and the reversal and resolution.

Suppose those exciting forces booster rockets were powerful enough to propel you through the Earth’s atmosphere and into outer space. You’re on the way to a quiet vacation on the moon and entering the middle of the journey, the longest and most dangerous part of your fictional Odyssey. Lots of things can go wrong here – battery dies, directional signals get screwed up, spacesuits leak – it is your job to keep all the parts tuned in working order so you can overcome the obstacles you confront, complete your mission and reach your destination.

Eight Approaches to Story Structure Your Story

- Keep it simple.

- Play it as it lays: make a few notes about your characters and scenes. Here, you are winging it, allowing one situation to lead to the next, which leads to the next. There’s not much-advanced planning, but there is room for spontaneity.

- Take baby steps. If dealing with the challenges of the plot, don’t you break your story into manageable segments to remove the intimidation from the task? Establish the primary story elements of the beginning, middle, and end. Then envision your narrative as an ongoing, interconnected chain of scenes and sequels. One causes a reaction that causes another action and reaction.

- What is the logical sequel to the scene?

- What action does the scene trigger that leads to the next scene?

- However, I planted the hook to pull the reader into the next scene.

- What is my hero done to move the story along?

- What is the next logical step in the story?

- How does the scene contribute to the larger context of the story?

- Create a literate outline. Before you write your book, break down each chapter into a white ball, noting which character situations are involved in each chapter. The outline will provide a map to follow and give you an overview of the book. Remember, however, that some of the most exciting journeys involve detours and unexpected sights. Even as you follow the map, stay open to surprises.

- Walk the North Forty. Develop a detailed chapter-by-chapter breakdown of your book, creating a visual map to follow. Once you grasp the overview, you can better understand what is happening in your story. When you see those places where you dropped the plot stitch or where one character hasn’t appeared in a while, you can pick up the thread before you move on.

- Decorate your wall. Make scene-by-scene notes 3” x 5” cards and arrange them on a bulletin board. The advantage of this method is that you can move your cards around, add some and toss others without messing up your overall story. Color coding characters and plot theme is helpful when using these methods because you can see what character, theme, or plot point is missing.

- Go classical. One of the old way of following classical story structures of Greek drama is from the exciting force of the climax to the resolution.

- Mix-and-match. Do your own thing. Consider all the different ways to structure your story and choose your preferred method. If you want to make scenes and sequels with a literary map, do it. Find the combination that’s right for you.

Holding the Reader’s Interest

For a story to succeed, the reader must be engrossed in each successive moment, care about what happens next, or at least be curious enough to want to know. When the reader is absorbed in every step, the next step is a fresh, and new experience. One of the tests of a good story is its ability to hold the reader in the present and every moment of his unfolding. How can this be achieved? The simplest form involves the reader wanting to discover what is unknown, to see the entire picture, or the complete action, after seeing its beginning. But you can’t count on the unknown alone to impel someone to keep reading. The reader must also care enough about the beginning to want to know the rest of the story.

One way to hold the reader’s interest is by introducing uncertainty or suspense. The nature of each picture or sequence in the unfolding of an action can contribute to the suspense.

When an actor drives at night on a road with unexpected turns, the stretch of road he can see at one time becomes shorter. The actor must watch the road carefully, and our suspense increases. The sequence is no longer predictable. We become concerned about the actor’s safety and wonder what will happen next. On his way home, he has to drive up a winding mountain road. The sky darkens. Heavy rain begins to fall. After a treacherous trip, he finally arrived safely home, where he could read his favorite picture book.

The logic of cause and effect explains how and why one event follows another.

But in other kinds of stories, not conforming to our life experience – fantasies, for example – we need the rigorous logic of cause and effect to accept that credibility. Otherwise, they may seem accidental or improbable, and we won’t care about them.